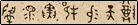

Question: Why is it that Hebrew, which is a language very very far removed from English, uses the to-infinitive; especially since no other language in this article (like Latin, Greek, French, Arabic, etc.) has it? Also, are there any other languages that have it?Hebrew has two infinitives, the infinitive absolute and the infinitive construct. The infinitive construct is used after prepositions and is inflected with pronominal endings to indicate its subject or object: bikhtōbh hassōphēr "when the scribe wrote", ahare lekhtō "after his going". When the infinitive construct is preceded by ל (lə-, li-, lā-) "to", it has a similar meaning as the English to-infinitive, and this is its most frequent use in Modern Hebrew. The infinitive absolute is used for verb focus, as in מות ימות mōth yāmūth (literally "die he will die"; figuratively, "he shall indeed die"). This usage is commonplace in the Bible, but in Modern Hebrew it is restricted to high-flown literary works.

Note, however, that the to-infinitive of Hebrew is not the dictionary form; that is the third person singular perfect form.

EDIT: By the way, Judaeo-Aramaic uses it too, although that's probably influenced by the Hebrew.