An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

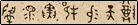

This is an idea I've had for a while, but haven't had a chance to do anything with in a concrete sense, so I thought I'd tell people about it: the Classical Lajhoran Script. Now, note: I've not been able to pin down some details of the language and its diachronics yet, and I've done nothing at all on the actual graphical design of the script; so I'm only going to be talking in conceptual terms, with made-up examples.

But the general idea is: some simple sound changes have made the orthography of Classical Lajhoran really, really weird.

Background

Lajhoran is a language, or family of languages, spoken across a very large empire, over a very long period of time. Like most empires, this empire has come and gone over the centuries, with periods of growth, retraction, stability, decentralisation, chaos, external conquest, reunification and so forth. The ancestral script was developed for a form of the language spoken around, say, 3500 years ago. I'm going to assume for this post that it was a syllabary (although I'm actually leaning toward it being some form of abugida, but it doesn't really matter for our purposes here).

Sometime around 1500-2000 years later, the empire entered its greatest period of decline; it ended up broken into an array of kingdoms, and there was a great deal of knowledge lost (a lot of libraries burned along the way, and so forth). We can think of this as not entirely unakin to the Fall of Rome, and the resulting Dark Age. Eventually, there was a reunification and resurgence, not only thanks to military strength, but also a general nostalgic yearning for the past - scholars dedicated to studying the ancient texts (such as remained), and the upper classes who funded them, formed the backbone of the new empire. This new empire further reinforced its unity and legitimacy through the standardisation of a new form of religion. And of course one priority for the new empire was establishing an official language, with which to enforce bureaucratic control, legal authority, and religious conformity.

Now, the original Ancient Lajhoran language evolved into Old Lajhoran, the language of the last stages of the 'old' empire, before the dark age. This shift was relatively... orderly. Old Lajhoran, while of course having its own dialects, was relatively uniform, as the universal empire, with centralised control and widespread trade (and military participation) encouraged everyone to maintain mutual intelligibility (and encouraged the replacement of local languages by Lajhoran). We can think here of something similar to the situation of Latin in the Roman Empire. And linguistically, the shifts over time at this point had been fairly minor: we're talking about Chaucer to today, not Bede to today. There would have been shifts in the grammar, in the vocabulary, and in the phonetic details, but someone fluent in Old Lajhoran could have read something written in Ancient Lajhoran, perhaps with a little training and a glossary of now-obscure words.

But like Chaucer for us, Ancient Lajhoran would have been more intelligible in writing than in speech, because of a simple sound shift: the loss of most unstressed vowels. Because the script was a syllabary (/abugida?), this vowel loss was not generally reflected in writing.

So, an Ancient word like, say, /tu'pe/, 'wing', becomes pronounced /tpe/, while /ku'ma/, 'fly', becomes /kma/, /ku'mana tes/, 'fly(ing) one', becomes /kmants/, 'flyer', /tar'gan/, 'stork', becomes /tr'ghan/, and /la'ti/ becomes /l'ti/. But these words are still written TU-PE, KU-MA, KU-MA-NA-TES, TAR-GAN and LA-TI. Some people probably even pronounce them that way in some contexts (reciting poetry, religious mantras, etc) - it's simply understood that, in practice, in 'vulgar speech', people don't actually pronounce all the vowels. All straightforward enough!

With the collapse of the old empire, we move into the era of Middle Lajhoran, and here some problems arise. Phonologically, the big transition here is that Old Lajhoran has a bunch of consonant clusters - particularly onset clusters - and these naturally simplify over time (perhaps they were already simplifying in particularly 'vulgar' casual Old Lajhoran). This MOSTLY happens the same way across at least the core of the language area, though perhaps not so much in outlying areas.

This causes semantic problems. TU-PE is now /p'e/ - but so are TA-PE and KO-PE. KU-MA is now /pa/ (denasal assimilation of the /m/ to the preceding /k/), but so is PA. LA-TI is now /di/, but so is RO-DI. In other words, there's been a massive lexical collapse, creating a huge number of homophonous monosyllables.

Now, many of these monosyllables are not really ambiguous, because their possible meanings would occur in totally different contexts, or because they come from different parts of speech. But a lot of them are, at least potentially, ambiguous. And this problem is resolved by the creation of new words for things, mostly by simply specifying through compounding. In Middle Lajhoran, you can now still talk about a /di/, 'bird', but to make extra clear you don't mean /di/, 'rat', you can instead say something like /p'edi/, 'wing-bird', or /pandi/, 'flying bird'. Over time, these less ambiguous forms tend to replace the simple forms, at least in ordinary speech (though less so in, for example, poetry).

However: there is no more empire at this point. Middle Lajhoran is really a family of languages, not a single form. Middle Lajhoran 'dialect' phonologies are fairly similar - trade hasn't completely broken down, and most dialects do continue to form a common linguistic area. But othe aspects of the language are different: the morphologies are different (Middle Lajhoran generally adds noun cases, for instance, but not always the same ones or from the same sources), and the lexicons are different. Specifically, people in different places have addressed the homophony problem in different ways. In some areas a bird is a /p'edi/; in others, a /pandi/; in others, a /pans/ (< kumana-tes). In some places it's even a /tar'khan/.

So what's the problem?

With the reformation of the empire, a new language standard was promulgated, Classical Lajhoran. Those who imposed it did not see themselves as creating a new language: they saw themselves as simply establishing (or even just confirming) a common written standard for the promulgation of authoritative texts (laws, charters, commands, religious documents, etc). In doing so, they faced three problems:

- vulgar speech had immorally degraded from the eternal classical standard, as people used coarse, ungainly, often illogical slang instead of the proper words. Why would anyone call something a 'wing bird' or a 'flying thing' when there's a perfectly good word for a bird? And don't they realise that a stork is a specific type of bird, not just any bird? Contrariwise, don't call a stork a 'big bird', call it a stork!

- speech was different in different places, as people used different slang terms from one another

- it wasn't always even clear how to go about writing the things that people said. There was very little popular tradition of writing in the Dark Age - most writing was done by scholars who were intentionally maintaining the old traditions. To the extent that people did write vernacular speech, it was in an ad hoc way, often with no great etymological rigour. With a word like /p'id@/, 'bird' (there has been further sound change!) - was that a TUPE LATI (wing bird) or a TUPE ROTI (wing rat)? Did ROTI even mean 'rat', or could it mean any small vertebrate? The ancient texts were not entirely clear. Or was it a KAPE ROTI, "pot [small vertebrate]", because it was, unlike real rats, good to eat? Or was it, as some people were spelling it, KUPE ROTI, "gold rat", because of a story in which a rat magically exchanged a pot of gold for the ability to fly?

All these problems could be dealt with by simply spelling everything as it damn well ought to be spelled, and if people wanted to use slang they could do that in their own time (i.e. out loud). So in Classical Lajhoran the word for 'bird' is simply spelled LA-TI, as it was in Ancient Lajhoran and in Old Lajhoran. This conveys the sense (relatively) unambiguously, and is equally comprehensible to everybody in the empire - you simply all have to learn that LA-TI means a bird, rather than having to remember that what you call a pida is called a penda over there, a pans in such-and-such a place, and even a tarkhan by some weirdos. And if you're a scholar who's been studying and recopying ancient texts, you damn well already know that, or you should. If you're not a scholar... you probably don't need to be reading texts anyway. You can find someone to read it to you if it's really essential, and you can ask them either to read it in a poetic/archaic way (calling a bird a 'di' and so on), which sounds pretty but is really hard to understand (both because you don't know all the words and because the ones you do know are ambiguous), or in an actually useful, practical way, using the 'slang' words for things current in your local area.

[however, written Classical Lajhoran is not actually the same as Old Lajhoran. Word order is different, and the Classical form does acknowledge some morphological features that were optional or absent in the Old form. Saying that you punched SE-LA-TI would mean you punched 'toward' a bird in Old Lajhoran (and would be odd), but that you punched a bird in Classical (and would be obligatory for every direct object). In addition, there are plenty of words in Classical Lajhoran in which nobody really knew how it would have been written in Old Lajhoran, due to the limited number of surviving texts, and the new generation of scholars simply had to guess, or plain invent.]

What this means

As a result, the Classical Lajhoran script has a number of oddities. Most obviously, the same word may be pronounced completely differently in different dialects, and not merely due to sound changes. More specifically, there are several interesting features:

- most CL roots are disyllabic, and are written with two characters. But there is usually no one-to-one equivalence between the character and the syllable. Disyllabic words mostly fall into one of four categories: those in which the second character is related to the sound and the first is not (typically from noun-noun and noun-verb compounds); those in which the first character is related to the sound and the second is not (typically from noun-adjective compounds); those in which neither character is related (where there has been complete suppletion); and those in which both characters are related (most often from original disyllables where the weak syllable was not completely reduce, or has been subsequently reinforced - TAR-GAN, for instance, is still /tarkhan/.

- the 'silent' character is not always useless, however. It often conveys MOA information, for example, although in a grossly overspecified way - so TU-PE means the second (although for another word it might be the first, or neither) syllable is /p'e/, but so does TA-PE, and KA-PE, and so on; whereas DA-PE and GA-PE both indicate /pe/, and TA-BE and KA-BE both indicate /phe/. Sometimes this rule breaks down, particularly where non-stops are involved, and the 'silent' character actually provides the POA instead.

- even the 'non-silent' character is not completely useful. Where it relates to the second syllable, the vowel has often been reduced to schwa (or another vowel, where is a coda); where it relates to the first syllable, there has often been umlaut, and sometimes consonant dissimilation. Thus, the word TO-DA is often pronounced /dether/, while the word KA-DA is typically pronounced /zuth@/, where the /de/ and /th@/ syllables are cognate, but have developed differently due to different contexts

- the 'true' pronunciation of a character-pair is sometimes seen in old names, where no compounding has occured in speech. But this is rather erratic, as many names have come to be spelled in fanciful ways, sometimes even incorporating unique characters.

- new characters have also arisen in certain common words. Old empire and dark age scribes would sometimes abbreviate common words by dropping a character - not always the more 'silent' character! - or, as a compromise, simplifying one character. These simplified characters have in some cases come to be used more widely as characters in their own right, while in other cases they have been incorporated into the non-reduced character of a word, forming a new character (a ligature that becomes an independent character).

- many words are written unetymologically - the 'silent' character is often altered to something more semantically logical, and sometimes this is even true of the 'spoken' character. For example, the word for 'feather' is etymologically RE-TYU (usually pronounced /podZ@/), but is instead typically spelled TU-DYU (which would be pronounced the same), so as to share the same silent character as TU-PE, 'wing'. Sometimes this yields diachronically 'wrong' pronounciations: instead of etymological GU-GA (/rog@/, 'float in air'), this word is instead written KU-GA, presumably to share a character with KU-MI, 'fly', although etymologically this 'should' yield a syllable /kh@/, not /g@/.

- this is even more of an issue with dialect terms. Writers of early Classical Lajhoran would sometimes wish to indicate a particular dialectical, 'slang' term, and would do so by writing out the term in full. Sometimes this has entered the language as a distinct word. Thus, in addition to LA-TI, 'bird', there is also the word KU-PE-RO-TI, 'stewed pigeon', spelling out the whole etymology as 'pot-rat'. In the capital region, both words are pronounced /pid@/, but in the West only the latter is /pid@/, while the former is /pand@/. As can be seen, words like this break down the two-characters-for-two-syllables paradigm.

- that gets worse in the case of a few words that entered the languages as 'spelled out slang', but that have become common words, as these are sometimes spelled as acronyms. Instead of writing out WE-TUS-GU-GA (literally 'water-float', 'to float on water'), the word /mduzg@/ (originally a dialectical equivalent to /rog@/, but now semantically distinct) is typically spelled simply WE-GA (though this 'ought' to be pronounced as the syllable /mkha/, which does not feature in the word /mduzg@/.

- even in writing, ambiguity can be a problem. It can be avoided by changing the spelling of a word to something else homophonous that has no other meaning... or it can be avoided through the addition of 'distinguishing marks' to a word, creating new characters.

- one interesting feature of the system is that internal morphophonological changes are not written, but external changes (affixes) are. For example, from /'tarkhan/, 'stork', is formed a collective form /'matikhan/, yet the latter is still written MA-TAR-GAN.

- affixes are in some cases written differently even when homophonous: the pluractional verb suffix -TA and the adjectival derivational suffix -TU are spelled differently, although both now represent simply /t/. On the other hand, the same suffix is always spelled the same way, even when pronounced differently: 'feather (accusative)' and 'bird (accusative)' are typically pronounced /sopodZ@/ and /sipid@/ respectively, yet are spelled with the same prefix, SE-.

- 'modern' loanwords are rare in writing - they're not that common in speech (it's the dominant language) and when they occur they're simply treated as dialect words. Ancient loanwords, however, are more problematic: generally they are still written as they were spelled in their own language (assuming it used the same or an equivalent script). These words may thus have undergone sound changes both within their own language AND within Lajhoran, which can mean that the relationship between writing and pronunciation is even more obscure than for native words.

- loans in the opposite direction, incidentally, are a nightmare. Earlier loanwords into other languages tended to transliterate the phonemic values of the characters and then treat the words as newly native; but later loanwords are often written in the Lajhoran script (much as some older or more pretentious English texts might insist on printing even single Greek loanwords in the Greek script), with the pronunciation reflecting the sound changes in the native language since the time of the borrowing, and the pronunciation of the word at that time in the dialect borrowed from (which can result in multiple pronunciations in the same recipient language, if the same 'word' was borrowed with different meanings and pronunciations at different times, or from different dialects). In a few cases, major neighbouring languages with long written histories use a hybrid solution: the word was transliterated and pronounced based on the Lajhoran pronunciation at the time (and in a certain dialect), but the same transliterated spelling continues to be used despite changes in both Lajhoran pronunciation AND the pronunciation of the recipient language - rather as though English continued to spell a word "armata", yet pronounce it "army".

- more generally, many minor languages without their own scripts simply employed the Lajhoran words logographically, giving them their own local pronunciations. In some cases these meta-Lajhoran scripts have since been simplified in various ways.

Conclusion

I don't really have one, sorry. I just think this is a fun idea!

But the general idea is: some simple sound changes have made the orthography of Classical Lajhoran really, really weird.

Background

Lajhoran is a language, or family of languages, spoken across a very large empire, over a very long period of time. Like most empires, this empire has come and gone over the centuries, with periods of growth, retraction, stability, decentralisation, chaos, external conquest, reunification and so forth. The ancestral script was developed for a form of the language spoken around, say, 3500 years ago. I'm going to assume for this post that it was a syllabary (although I'm actually leaning toward it being some form of abugida, but it doesn't really matter for our purposes here).

Sometime around 1500-2000 years later, the empire entered its greatest period of decline; it ended up broken into an array of kingdoms, and there was a great deal of knowledge lost (a lot of libraries burned along the way, and so forth). We can think of this as not entirely unakin to the Fall of Rome, and the resulting Dark Age. Eventually, there was a reunification and resurgence, not only thanks to military strength, but also a general nostalgic yearning for the past - scholars dedicated to studying the ancient texts (such as remained), and the upper classes who funded them, formed the backbone of the new empire. This new empire further reinforced its unity and legitimacy through the standardisation of a new form of religion. And of course one priority for the new empire was establishing an official language, with which to enforce bureaucratic control, legal authority, and religious conformity.

Now, the original Ancient Lajhoran language evolved into Old Lajhoran, the language of the last stages of the 'old' empire, before the dark age. This shift was relatively... orderly. Old Lajhoran, while of course having its own dialects, was relatively uniform, as the universal empire, with centralised control and widespread trade (and military participation) encouraged everyone to maintain mutual intelligibility (and encouraged the replacement of local languages by Lajhoran). We can think here of something similar to the situation of Latin in the Roman Empire. And linguistically, the shifts over time at this point had been fairly minor: we're talking about Chaucer to today, not Bede to today. There would have been shifts in the grammar, in the vocabulary, and in the phonetic details, but someone fluent in Old Lajhoran could have read something written in Ancient Lajhoran, perhaps with a little training and a glossary of now-obscure words.

But like Chaucer for us, Ancient Lajhoran would have been more intelligible in writing than in speech, because of a simple sound shift: the loss of most unstressed vowels. Because the script was a syllabary (/abugida?), this vowel loss was not generally reflected in writing.

So, an Ancient word like, say, /tu'pe/, 'wing', becomes pronounced /tpe/, while /ku'ma/, 'fly', becomes /kma/, /ku'mana tes/, 'fly(ing) one', becomes /kmants/, 'flyer', /tar'gan/, 'stork', becomes /tr'ghan/, and /la'ti/ becomes /l'ti/. But these words are still written TU-PE, KU-MA, KU-MA-NA-TES, TAR-GAN and LA-TI. Some people probably even pronounce them that way in some contexts (reciting poetry, religious mantras, etc) - it's simply understood that, in practice, in 'vulgar speech', people don't actually pronounce all the vowels. All straightforward enough!

With the collapse of the old empire, we move into the era of Middle Lajhoran, and here some problems arise. Phonologically, the big transition here is that Old Lajhoran has a bunch of consonant clusters - particularly onset clusters - and these naturally simplify over time (perhaps they were already simplifying in particularly 'vulgar' casual Old Lajhoran). This MOSTLY happens the same way across at least the core of the language area, though perhaps not so much in outlying areas.

This causes semantic problems. TU-PE is now /p'e/ - but so are TA-PE and KO-PE. KU-MA is now /pa/ (denasal assimilation of the /m/ to the preceding /k/), but so is PA. LA-TI is now /di/, but so is RO-DI. In other words, there's been a massive lexical collapse, creating a huge number of homophonous monosyllables.

Now, many of these monosyllables are not really ambiguous, because their possible meanings would occur in totally different contexts, or because they come from different parts of speech. But a lot of them are, at least potentially, ambiguous. And this problem is resolved by the creation of new words for things, mostly by simply specifying through compounding. In Middle Lajhoran, you can now still talk about a /di/, 'bird', but to make extra clear you don't mean /di/, 'rat', you can instead say something like /p'edi/, 'wing-bird', or /pandi/, 'flying bird'. Over time, these less ambiguous forms tend to replace the simple forms, at least in ordinary speech (though less so in, for example, poetry).

However: there is no more empire at this point. Middle Lajhoran is really a family of languages, not a single form. Middle Lajhoran 'dialect' phonologies are fairly similar - trade hasn't completely broken down, and most dialects do continue to form a common linguistic area. But othe aspects of the language are different: the morphologies are different (Middle Lajhoran generally adds noun cases, for instance, but not always the same ones or from the same sources), and the lexicons are different. Specifically, people in different places have addressed the homophony problem in different ways. In some areas a bird is a /p'edi/; in others, a /pandi/; in others, a /pans/ (< kumana-tes). In some places it's even a /tar'khan/.

So what's the problem?

With the reformation of the empire, a new language standard was promulgated, Classical Lajhoran. Those who imposed it did not see themselves as creating a new language: they saw themselves as simply establishing (or even just confirming) a common written standard for the promulgation of authoritative texts (laws, charters, commands, religious documents, etc). In doing so, they faced three problems:

- vulgar speech had immorally degraded from the eternal classical standard, as people used coarse, ungainly, often illogical slang instead of the proper words. Why would anyone call something a 'wing bird' or a 'flying thing' when there's a perfectly good word for a bird? And don't they realise that a stork is a specific type of bird, not just any bird? Contrariwise, don't call a stork a 'big bird', call it a stork!

- speech was different in different places, as people used different slang terms from one another

- it wasn't always even clear how to go about writing the things that people said. There was very little popular tradition of writing in the Dark Age - most writing was done by scholars who were intentionally maintaining the old traditions. To the extent that people did write vernacular speech, it was in an ad hoc way, often with no great etymological rigour. With a word like /p'id@/, 'bird' (there has been further sound change!) - was that a TUPE LATI (wing bird) or a TUPE ROTI (wing rat)? Did ROTI even mean 'rat', or could it mean any small vertebrate? The ancient texts were not entirely clear. Or was it a KAPE ROTI, "pot [small vertebrate]", because it was, unlike real rats, good to eat? Or was it, as some people were spelling it, KUPE ROTI, "gold rat", because of a story in which a rat magically exchanged a pot of gold for the ability to fly?

All these problems could be dealt with by simply spelling everything as it damn well ought to be spelled, and if people wanted to use slang they could do that in their own time (i.e. out loud). So in Classical Lajhoran the word for 'bird' is simply spelled LA-TI, as it was in Ancient Lajhoran and in Old Lajhoran. This conveys the sense (relatively) unambiguously, and is equally comprehensible to everybody in the empire - you simply all have to learn that LA-TI means a bird, rather than having to remember that what you call a pida is called a penda over there, a pans in such-and-such a place, and even a tarkhan by some weirdos. And if you're a scholar who's been studying and recopying ancient texts, you damn well already know that, or you should. If you're not a scholar... you probably don't need to be reading texts anyway. You can find someone to read it to you if it's really essential, and you can ask them either to read it in a poetic/archaic way (calling a bird a 'di' and so on), which sounds pretty but is really hard to understand (both because you don't know all the words and because the ones you do know are ambiguous), or in an actually useful, practical way, using the 'slang' words for things current in your local area.

[however, written Classical Lajhoran is not actually the same as Old Lajhoran. Word order is different, and the Classical form does acknowledge some morphological features that were optional or absent in the Old form. Saying that you punched SE-LA-TI would mean you punched 'toward' a bird in Old Lajhoran (and would be odd), but that you punched a bird in Classical (and would be obligatory for every direct object). In addition, there are plenty of words in Classical Lajhoran in which nobody really knew how it would have been written in Old Lajhoran, due to the limited number of surviving texts, and the new generation of scholars simply had to guess, or plain invent.]

What this means

As a result, the Classical Lajhoran script has a number of oddities. Most obviously, the same word may be pronounced completely differently in different dialects, and not merely due to sound changes. More specifically, there are several interesting features:

- most CL roots are disyllabic, and are written with two characters. But there is usually no one-to-one equivalence between the character and the syllable. Disyllabic words mostly fall into one of four categories: those in which the second character is related to the sound and the first is not (typically from noun-noun and noun-verb compounds); those in which the first character is related to the sound and the second is not (typically from noun-adjective compounds); those in which neither character is related (where there has been complete suppletion); and those in which both characters are related (most often from original disyllables where the weak syllable was not completely reduce, or has been subsequently reinforced - TAR-GAN, for instance, is still /tarkhan/.

- the 'silent' character is not always useless, however. It often conveys MOA information, for example, although in a grossly overspecified way - so TU-PE means the second (although for another word it might be the first, or neither) syllable is /p'e/, but so does TA-PE, and KA-PE, and so on; whereas DA-PE and GA-PE both indicate /pe/, and TA-BE and KA-BE both indicate /phe/. Sometimes this rule breaks down, particularly where non-stops are involved, and the 'silent' character actually provides the POA instead.

- even the 'non-silent' character is not completely useful. Where it relates to the second syllable, the vowel has often been reduced to schwa (or another vowel, where is a coda); where it relates to the first syllable, there has often been umlaut, and sometimes consonant dissimilation. Thus, the word TO-DA is often pronounced /dether/, while the word KA-DA is typically pronounced /zuth@/, where the /de/ and /th@/ syllables are cognate, but have developed differently due to different contexts

- the 'true' pronunciation of a character-pair is sometimes seen in old names, where no compounding has occured in speech. But this is rather erratic, as many names have come to be spelled in fanciful ways, sometimes even incorporating unique characters.

- new characters have also arisen in certain common words. Old empire and dark age scribes would sometimes abbreviate common words by dropping a character - not always the more 'silent' character! - or, as a compromise, simplifying one character. These simplified characters have in some cases come to be used more widely as characters in their own right, while in other cases they have been incorporated into the non-reduced character of a word, forming a new character (a ligature that becomes an independent character).

- many words are written unetymologically - the 'silent' character is often altered to something more semantically logical, and sometimes this is even true of the 'spoken' character. For example, the word for 'feather' is etymologically RE-TYU (usually pronounced /podZ@/), but is instead typically spelled TU-DYU (which would be pronounced the same), so as to share the same silent character as TU-PE, 'wing'. Sometimes this yields diachronically 'wrong' pronounciations: instead of etymological GU-GA (/rog@/, 'float in air'), this word is instead written KU-GA, presumably to share a character with KU-MI, 'fly', although etymologically this 'should' yield a syllable /kh@/, not /g@/.

- this is even more of an issue with dialect terms. Writers of early Classical Lajhoran would sometimes wish to indicate a particular dialectical, 'slang' term, and would do so by writing out the term in full. Sometimes this has entered the language as a distinct word. Thus, in addition to LA-TI, 'bird', there is also the word KU-PE-RO-TI, 'stewed pigeon', spelling out the whole etymology as 'pot-rat'. In the capital region, both words are pronounced /pid@/, but in the West only the latter is /pid@/, while the former is /pand@/. As can be seen, words like this break down the two-characters-for-two-syllables paradigm.

- that gets worse in the case of a few words that entered the languages as 'spelled out slang', but that have become common words, as these are sometimes spelled as acronyms. Instead of writing out WE-TUS-GU-GA (literally 'water-float', 'to float on water'), the word /mduzg@/ (originally a dialectical equivalent to /rog@/, but now semantically distinct) is typically spelled simply WE-GA (though this 'ought' to be pronounced as the syllable /mkha/, which does not feature in the word /mduzg@/.

- even in writing, ambiguity can be a problem. It can be avoided by changing the spelling of a word to something else homophonous that has no other meaning... or it can be avoided through the addition of 'distinguishing marks' to a word, creating new characters.

- one interesting feature of the system is that internal morphophonological changes are not written, but external changes (affixes) are. For example, from /'tarkhan/, 'stork', is formed a collective form /'matikhan/, yet the latter is still written MA-TAR-GAN.

- affixes are in some cases written differently even when homophonous: the pluractional verb suffix -TA and the adjectival derivational suffix -TU are spelled differently, although both now represent simply /t/. On the other hand, the same suffix is always spelled the same way, even when pronounced differently: 'feather (accusative)' and 'bird (accusative)' are typically pronounced /sopodZ@/ and /sipid@/ respectively, yet are spelled with the same prefix, SE-.

- 'modern' loanwords are rare in writing - they're not that common in speech (it's the dominant language) and when they occur they're simply treated as dialect words. Ancient loanwords, however, are more problematic: generally they are still written as they were spelled in their own language (assuming it used the same or an equivalent script). These words may thus have undergone sound changes both within their own language AND within Lajhoran, which can mean that the relationship between writing and pronunciation is even more obscure than for native words.

- loans in the opposite direction, incidentally, are a nightmare. Earlier loanwords into other languages tended to transliterate the phonemic values of the characters and then treat the words as newly native; but later loanwords are often written in the Lajhoran script (much as some older or more pretentious English texts might insist on printing even single Greek loanwords in the Greek script), with the pronunciation reflecting the sound changes in the native language since the time of the borrowing, and the pronunciation of the word at that time in the dialect borrowed from (which can result in multiple pronunciations in the same recipient language, if the same 'word' was borrowed with different meanings and pronunciations at different times, or from different dialects). In a few cases, major neighbouring languages with long written histories use a hybrid solution: the word was transliterated and pronounced based on the Lajhoran pronunciation at the time (and in a certain dialect), but the same transliterated spelling continues to be used despite changes in both Lajhoran pronunciation AND the pronunciation of the recipient language - rather as though English continued to spell a word "armata", yet pronounce it "army".

- more generally, many minor languages without their own scripts simply employed the Lajhoran words logographically, giving them their own local pronunciations. In some cases these meta-Lajhoran scripts have since been simplified in various ways.

Conclusion

I don't really have one, sorry. I just think this is a fun idea!

- Creyeditor

- MVP

- Posts: 5124

- Joined: 14 Aug 2012 19:32

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

That sounds great and well thought out. Two questions:

- You compare this to Latin, but isn't ut more similar to Chinese? The script being lost, but the pronunciations varying greatly and stuff ...

- Would you still classify the modern version of the script as an abiguda? Or is it more of a logographic system with a phonetic component?

Creyeditor

"Thoughts are free."

Produce, Analyze, Manipulate

1 2

2  3

3  4

4  4

4

Ook & Omlűt & Nautli languages & Sperenjas

Ook & Omlűt & Nautli languages & Sperenjas

![<3 [<3]](./images/smilies/heartic.png) Papuan languages, Morphophonology, Lexical Semantics

Papuan languages, Morphophonology, Lexical Semantics ![<3 [<3]](./images/smilies/heartic.png)

"Thoughts are free."

Produce, Analyze, Manipulate

1

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

Well, the Latin analogy is just from the perspective of English speakers, and the cultural role of Latin. Yes, in many ways it's more like Chinese. Which is probably part of why I try to compare it to Latin (because I don't want it just to become Chinese).

And yes, the idea is that it does effectively become a logography - but that it does so from a segmental direction, rather than through direct descent from pictograms. [it's easy to assume a constant evolution: pictograms > logography > syllabary > abjad > alphabet. But occasionally things could go the other way...]. But it's a logography with, as you say, a considerable phonetic aspect to it. For instance, other than some assimilation/dissimilation effects, affixes are effectively spelled phonetically (albeit in a many>one way). And generally (where there isn't shorthand or unetymological spelling) at least half the syllables of the word are perfectly phonetically predictable... it's just that the others aren't even vaguely indicated...

[fwiw, the 'modern' time period is something like another 1,200 years after this system was created. By this point, the dialects really are independent languages, and the 'classical' language is not so much a bad way of spelling the 'dialects' as just a completely different language that is only written and not spoken. Although there was at one point a 'neoclassical' revival movement at court, which attempted to impose an anachronistic phonetic pronunciation onto the classical characters.]

I also meant to say out loud: although people might think "but when these letters denoted characters that had been dropped, why weren't the letters dropped?", there was good reason for keeping them. When the vowels were dropped, these characters still showed the consonants. And when the consonants were dropped, phonological processes caused them to influence adjacent consonants. Due to subsequent changes in MOA, some modern phonemes only descend from those clusters, and so can't be spelled phonetically with single characters: although the /l/ of LATI has been dropped, you can't just drop the LA, because TI would be /ti/, not /di/.

And yes, the idea is that it does effectively become a logography - but that it does so from a segmental direction, rather than through direct descent from pictograms. [it's easy to assume a constant evolution: pictograms > logography > syllabary > abjad > alphabet. But occasionally things could go the other way...]. But it's a logography with, as you say, a considerable phonetic aspect to it. For instance, other than some assimilation/dissimilation effects, affixes are effectively spelled phonetically (albeit in a many>one way). And generally (where there isn't shorthand or unetymological spelling) at least half the syllables of the word are perfectly phonetically predictable... it's just that the others aren't even vaguely indicated...

[fwiw, the 'modern' time period is something like another 1,200 years after this system was created. By this point, the dialects really are independent languages, and the 'classical' language is not so much a bad way of spelling the 'dialects' as just a completely different language that is only written and not spoken. Although there was at one point a 'neoclassical' revival movement at court, which attempted to impose an anachronistic phonetic pronunciation onto the classical characters.]

I also meant to say out loud: although people might think "but when these letters denoted characters that had been dropped, why weren't the letters dropped?", there was good reason for keeping them. When the vowels were dropped, these characters still showed the consonants. And when the consonants were dropped, phonological processes caused them to influence adjacent consonants. Due to subsequent changes in MOA, some modern phonemes only descend from those clusters, and so can't be spelled phonetically with single characters: although the /l/ of LATI has been dropped, you can't just drop the LA, because TI would be /ti/, not /di/.

- Creyeditor

- MVP

- Posts: 5124

- Joined: 14 Aug 2012 19:32

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

I like how this is similar to the claim that English is slowly evolving towards a logographic system. Of course, your concept is much clearer.

Creyeditor

"Thoughts are free."

Produce, Analyze, Manipulate

1 2

2  3

3  4

4  4

4

Ook & Omlűt & Nautli languages & Sperenjas

Ook & Omlűt & Nautli languages & Sperenjas

![<3 [<3]](./images/smilies/heartic.png) Papuan languages, Morphophonology, Lexical Semantics

Papuan languages, Morphophonology, Lexical Semantics ![<3 [<3]](./images/smilies/heartic.png)

"Thoughts are free."

Produce, Analyze, Manipulate

1

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

This reminds me almost of Tibetan, but with a syllabary rather than an abugida, and a much greater importance regarding the role of the "pre-initial" (or, in this case, first syllable), and a hint of the sort of compound seen in Mandarin and related languages

IIRC, the "root consonants", when looking at the plosives and affricates, at least, are either aspirated (represented in writing by an "aspirate" high tone and a "voiced" low tone set of syllabic signs) or unaspirated (represented just by the "voiceless" high tone set). When there's a pre-initial (', b, d, g, or m), the aspirates becoming unaspirated, maintaining their tone (in addition, nasal roots, which by default take the low tone, take the high tone instead). Similarly, when there's a superscript consonant (r, l, or s), the "voiced" set lose their aspiration (sometimes even becoming fully voiced), and, from what I can tell, maintain their low tone, but I'm not 100% sure on that.

The subscript l, r, w, y are where you tend to see the biggest effect on the pronunciation of the root consonant in terms of things being MOA (for example, all of pr, tr, and kr appear to end up merging into /ʈʂ/, and py ends up merging into /tɕ/ alongside plain c, while subscript l causes the root consonant to go unpronounced, leaving just /l/ in all instances, while w goes in the opposite direction and doesn't get pronounced at all, with no effect on the root consonant)

And then the suffixes end up either being pronounced, unpronounced while modifying the previous vowel, or both, with the secondary suffixes that come after affecting the tone of the syllable (they seem to lead to contour tones)

Because of the way sound changes have effected the sounds of words, including inflected forms, this also means that what was once an addition of a prefix or a suffix (or a secondary suffix), despite still being represented as such in writing, is now marked in speech by a change in aspiration, vowel quality, vowel length, or tone, or even some combination of these factors.

That's just in Lhasa Tibetan, though (and only one dialect, I think). Other Tibetic languages, some of which I think still, like Lhasa, basically write as if they're writing in Old Tibetan, have, because of sound changes over the millennium or so, ended up with different situations in which the pronunciation doesn't match the written word (some preserve more the the superscript consonants in initial consonant clusters, some have developed different vowels, others have preserved more of the final consonants, etc.)

So, at least using that as an example, I could see the system you've proposed being pretty reasonable, although using a full syllabary, where the full vocalisation of all of the syllables in the older form of the language are preserved, with irregularities from slang and borrowings (as well as the meddling of scribes), does make it even more interesting.

It also reminds me, to a point, or the use of Akkadian cuneiform being used in Hittite, where a word might have been spelt out in syllables that reflect the Akkadian pronunciation, but used in Hittite, and read, presumably, in Hittite (although I suspect this crosses more into the "syllabary becomes a logography" territory than your idea)

IIRC, the "root consonants", when looking at the plosives and affricates, at least, are either aspirated (represented in writing by an "aspirate" high tone and a "voiced" low tone set of syllabic signs) or unaspirated (represented just by the "voiceless" high tone set). When there's a pre-initial (', b, d, g, or m), the aspirates becoming unaspirated, maintaining their tone (in addition, nasal roots, which by default take the low tone, take the high tone instead). Similarly, when there's a superscript consonant (r, l, or s), the "voiced" set lose their aspiration (sometimes even becoming fully voiced), and, from what I can tell, maintain their low tone, but I'm not 100% sure on that.

The subscript l, r, w, y are where you tend to see the biggest effect on the pronunciation of the root consonant in terms of things being MOA (for example, all of pr, tr, and kr appear to end up merging into /ʈʂ/, and py ends up merging into /tɕ/ alongside plain c, while subscript l causes the root consonant to go unpronounced, leaving just /l/ in all instances, while w goes in the opposite direction and doesn't get pronounced at all, with no effect on the root consonant)

And then the suffixes end up either being pronounced, unpronounced while modifying the previous vowel, or both, with the secondary suffixes that come after affecting the tone of the syllable (they seem to lead to contour tones)

Because of the way sound changes have effected the sounds of words, including inflected forms, this also means that what was once an addition of a prefix or a suffix (or a secondary suffix), despite still being represented as such in writing, is now marked in speech by a change in aspiration, vowel quality, vowel length, or tone, or even some combination of these factors.

That's just in Lhasa Tibetan, though (and only one dialect, I think). Other Tibetic languages, some of which I think still, like Lhasa, basically write as if they're writing in Old Tibetan, have, because of sound changes over the millennium or so, ended up with different situations in which the pronunciation doesn't match the written word (some preserve more the the superscript consonants in initial consonant clusters, some have developed different vowels, others have preserved more of the final consonants, etc.)

So, at least using that as an example, I could see the system you've proposed being pretty reasonable, although using a full syllabary, where the full vocalisation of all of the syllables in the older form of the language are preserved, with irregularities from slang and borrowings (as well as the meddling of scribes), does make it even more interesting.

It also reminds me, to a point, or the use of Akkadian cuneiform being used in Hittite, where a word might have been spelt out in syllables that reflect the Akkadian pronunciation, but used in Hittite, and read, presumably, in Hittite (although I suspect this crosses more into the "syllabary becomes a logography" territory than your idea)

You can tell the same lie a thousand times,

But it never gets any more true,

So close your eyes once more and once more believe

That they all still believe in you.

Just one time.

But it never gets any more true,

So close your eyes once more and once more believe

That they all still believe in you.

Just one time.

-

Nortaneous

- greek

- Posts: 676

- Joined: 14 Aug 2010 13:28

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

hm, if writing is old enough in the Allosphere I could steal this for Zzyxwqnp, although I'm not sure what the writing situation is

Yes, and some Rgyalrongic languages (not closely related but phonologically similar to Old Tibetan and bearing a great number of Tibetan loanwords) have recently started to be written in the Tibetan script, although I can't remember where I read about this. Generally the Tibetan lexical stratum in Rgyalrongic is much more phonologically conservative than most Tibetic varieties.sangi39 wrote: ↑04 Feb 2022 23:54 That's just in Lhasa Tibetan, though (and only one dialect, I think). Other Tibetic languages, some of which I think still, like Lhasa, basically write as if they're writing in Old Tibetan, have, because of sound changes over the millennium or so, ended up with different situations in which the pronunciation doesn't match the written word (some preserve more the the superscript consonants in initial consonant clusters, some have developed different vowels, others have preserved more of the final consonants, etc.)

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

Thanks, yes, both of you, I'd actually thought of Tibetan when thinking about Old Lajhoran's appearance, although I didn't know the details of how modern Tibetan actually dealt with those clusters.

I've been toying with the idea of, as you say, marking some morphological distinction through an MOA change descending from a prefix, but I'm not sure I'll go through with that - Old Lajhoran I think was probably pretty isolating, so I'm not sure what distinction would be appropriate. As I say, there's a lot of work still needing to be done on the actual details of the language...

I've been toying with the idea of, as you say, marking some morphological distinction through an MOA change descending from a prefix, but I'm not sure I'll go through with that - Old Lajhoran I think was probably pretty isolating, so I'm not sure what distinction would be appropriate. As I say, there's a lot of work still needing to be done on the actual details of the language...

-

Zythros Jubi

- sinic

- Posts: 417

- Joined: 24 Nov 2014 17:31

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

Guillaume Jacques mentioned this in A Grammar of Japhug.Nortaneous wrote: ↑04 Feb 2022 23:54 Yes, and some Rgyalrongic languages (not closely related but phonologically similar to Old Tibetan and bearing a great number of Tibetan loanwords) have recently started to be written in the Tibetan script, although I can't remember where I read about this. Generally the Tibetan lexical stratum in Rgyalrongic is much more phonologically conservative than most Tibetic varieties.

Lostlang plans: Oghur Turkic, Gallaecian Celtic, Palaeo-Balkanic

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

It reminded me of Tibetan, too, especially since I'm making a language inspired by Tibetan (though there is Mayan influence on certain aspects of the language) and the abugida is such that, thus ,in my conlang the syllable /t͡ɕo˧˥/ can be written in the following ways:

<t͡sjop t͡sjok tjop tjok kjop kjok t͡slop t͡slok>

And ʈ͡ʂi˧˩/ as so:

/bɹis bɹix bɻis bɻix ɓɹi ɓɻi dɹis dɹix dɻis dɻix ɗɹi ɗɻi d͜zɹɹis d͜zɹix d͜zɻis d͜zɻix gɹis gɹix gɻis gɻix ɠɹi ɠɻi>

Many children make up, or begin to make up, imaginary languages. I have been at it since I could write.

-JRR Tolkien

-JRR Tolkien

-

Nortaneous

- greek

- Posts: 676

- Joined: 14 Aug 2010 13:28

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

As a reference to the widespread Sino-Tibetan s-causative, right?Salmoneus wrote: ↑06 Feb 2022 23:12 I've been toying with the idea of, as you say, marking some morphological distinction through an MOA change descending from a prefix, but I'm not sure I'll go through with that - Old Lajhoran I think was probably pretty isolating, so I'm not sure what distinction would be appropriate.

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

I'm interested to see where this goes. I'm also wondering how long people would put up with such an unwieldy system. If it saw increased usage among common people, informal, more phonetic spellings might eventually start to gain popularity, at least for some of the most unintuitive spellings.

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

And the several different verbal affixes that have produced initial voicing/prenasalisation and then disappeared in different Austronesian branches. But yes, I was specifically considering an s-prefix of some sort.Nortaneous wrote: ↑13 Feb 2022 04:14As a reference to the widespread Sino-Tibetan s-causative, right?Salmoneus wrote: ↑06 Feb 2022 23:12 I've been toying with the idea of, as you say, marking some morphological distinction through an MOA change descending from a prefix, but I'm not sure I'll go through with that - Old Lajhoran I think was probably pretty isolating, so I'm not sure what distinction would be appropriate.

Re: An Unusual Orthography (Concept)

I am also wondering this.clawgrip wrote: ↑15 Feb 2022 04:38 I'm interested to see where this goes. I'm also wondering how long people would put up with such an unwieldy system. If it saw increased usage among common people, informal, more phonetic spellings might eventually start to gain popularity, at least for some of the most unintuitive spellings.

The complication here is that before too long this becomes a writing system for... no spoken language at all. Classical Lajhoran continues to be used as a written standard for another thousand years or more, while spoken language diverges not only morphologically and phonemically but also syntactically. So there's no great impulse to make the spelling reflect any pronunciation, because it's seen as its own language. As an analogy, people continued writing Latin with Classical spelling long, long after spoken French stopped sounding anything like Latin.

However, that of course leaves the question of whether people would need to write their own vernacular as well and, if so, how they would spell it. I actually know that at least two other Lajhoran descendents are also used as lingua francas*, and they must be written somehow, but i'm not sure how, and I'm not sure whether vernaculars themselves will eventually be written. I'm leaning toward 'yes', but I'm not sure of the history or sociology of that.

[as for how: options include a modified semi-logography adapted from Classical but with vernacular word orders and affixes and possibly new spellings for local words, a syllabary (or abugida) produced by radically simplifying the Classical system, or by re-importing a system from outside Classical (from a neighbouring or peripheral area), that bypasses a lot of those changes and preserves older values. Or just by using an entirely different writing system borrowed from neighbours.]

*one originates as a peripheral dialect that was spoken around 800 years ago by a provincial family who rose to power over the empire; their dialect/language became the standard among their court in the capital and remained so for centuries, diverging from the actual peripheral dialect; this court standard has now died out as a spoken language, but its period of fashionable dominance lead it to be the language used in early popular novels, and it continues as the language of art and literature in a purely written form. It's a little like French in Early Modern Europe: Latin/Classical are used for scholarly treatises and official texts, but French/this language are used for poetry and novels and memoires. The other lingua franca emerged from the capital itself, mostly, and is a trade-focused koine that adopts some capital features while levelling out others to produce something that can be understood by merchants and minor officials thoughout the empire; this is used in speech, but is nobody's first language anymore, as the dialect of the capital has moved on since it was developed. This was at one point a little sociologically like Mandarin, although in the last century and a half the goverment has tried to return to Classical as a backlash against the mercantile classes and their perceived excessive power.

[*sigh* yes, I've made this all much too complicated for myself...]